During the mid-20th Century and before, the playground behind St. Joseph’s “Old School” in Bonneauville was bare earth. The ground was hard-packed and smooth, with a light coating of the finest dust. It was the perfect surface for playing marbles.

In the 1950’s, at recess and lunch time, a circle of three to six feet or more in diameter was scribed in the dirt with a stick or stone as quickly as the boys could get out through the school door. Some guys were good at creating a nearly perfect circle in one deft rotating motion. The ring size was never measured. It was decided by whatever whim ruled the day and by the approximate number of players.

To begin the game each player dropped the same number of marbles randomly from about waist height, near the center of the ring. I do not recall the process for determining the order in which each shooter played but it was a fair and uncontested system.

Each player in turn placed his favorite shooter (often a chipped-up marble for better grip) between the thumb and index finger and shot (or “eye bombed” if he so chose). Guys who played often developed a callus on the skin behind the thumbnail, with a peeling back of the cuticle there. A bit of playground dust that clung to the shooter marble became impacted underneath the cuticle to the point of slight discomfort. The single pea sized callus was a badge of honor. Based on the condition of the thumb one could easily tell who the most avid marble players were.

There was the distinct almost metallic sound each time one small glass sphere struck another. If the first shooter hit a marble outside of the circle, he picked up the marble and kept it. He then shot again from the spot where his shooter marble landed inside the circle, or from anywhere on the rim of the circle, until he failed to hit a marble out of the ring. Then the second in order was up, and so on.

The norm was to “knuckle down,” that is, to place the knuckles on the ground to steady the aim. If the boy shooting was fond of a nice marble, say someone else’s favorite shooter marble that was stuck in the ring behind another marble; he could risk shooting from any height.

For a straight down shot, called “eye bombers,” gravity ruled. A larger marble was sighted by the boy standing directly over the target. The hope was that a ricochet would propel the target marble at right angle across the ground and out of the ring. It was a bold move.

The game was nearly always played “for keeps” which meant that at the end of the game everyone got to keep the marbles they knocked out. When a player lost all of his marbles (lost his marbles,) he was out of the game.

Different size marbles were used for advantage. Peewees (about 3/8” diameter) were smaller marbles that were less expensive, less attractive, not as desirable and harder to hit. Still they played a role in the strategy of the game. Large shooters (up to about 1” in diameter) were used. There was much strategy in a game of marbles but it was often more instinctive than calculated.

The games left the best players with a surplus of marbles. They were usually carried in a pants pocket; never in the little cloth bag with a draw string that was popular in earlier times when clay marbles were popular.

*****

The Bonneauville Fire Company Water Reservoir was located about one-half block south-west of the school playground. A goodly percentage of youngsters passed “The Dam” as the reservoir was commonly known, on their way home from school daily. Some of those student’s pockets fairly bulged with marbles.

As is the nature of young people, the marble champs liked to splash objects in the water. They loved skipping stones or even more challenging perhaps; marbles. Like lighting a cigar with a dollar bill in the 50’s it was a bit egotistic to throw away precious marbles, especially cats eyes and bumble bees. But it certainly did demonstrate with a bit of youthful flair, and whom were the best players.

The dam was filled with rainwater runoff from the farms and homes along Maple Street. Mixed with the runoff were top soil granules, leaf matter, and less desirable particulates-mostly from backyard burning barrels.

Occasionally the dam had to be drained and dredged. The process could easily double the volume of a body of water (needed to fight fires). The dredged sludge was desirable to farmers who gladly used it to fill in eroded soil areas on their farms.

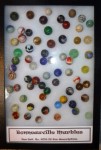

Around 1970 Bonneauville farmer Ambrose Myers, who at that time had served nearly fifty years with the fire company, was the recipient of the Dam’s sediment. The goopy mix was placed in a hollow near the west border of his hundred-acre farm. For years after, farm hands, too young to remember the Dam, which had been filled-in when the Borough installed city sewer, water and fire hydrants, gathered jars of marbles. Marbles can still be found after a newly planted field has been rained on a few times to expose the brilliant reds, blues and yellows and combinations of the primary colors swirling through the glass.

The Old School yard playground was bordered to the east by a corn field. The fact that the unfenced field was off limits to students did not always mean that it remained unvisited during the century or so that the school remained operable. When that field was plowed, marbles could also be found. Other marbles of this collection were found in the cemetery, in the soil of the alleyway that connects the playground with Maple Street, and in the garden of a home on Maple Street that was built just after the Civil War.

*****

At the lower right hand corner of this display are four small ceramic tiles. They were found with the marbles in Mr. Myers farm field. What ceramic tiles were doing hanging out below ground in a farm field with marbles seems a bit curious.

In the mid-20th Century there were several ceramic tile manufacturing facilities in and around Gettysburg, PA. There always seemed to be an over-abundance of defective and damaged tiles piled by the dump truck load in front of the factories. There was more than enough tiles to make a very young lad wonder how such a large percentage of product could be wasted, and a factory still stay in business.

WWII had been over for several years and the economy was doing well. Houses were being built. Still, with the large Catholic families of Bonneauville, money needed to be conserved whenever possible. The tile factories offered their rejects for sale to locals as a home and commercial driveway paving material. Several homes of the town could at one time or another, be seen sporting the colorful material as an economic substitute for crushed quarry stone. Vince Staub, then owner of the auto repair garage that stood beside the water reservoir, had a few loads hauled in to pave the "Back Alley" between his garage and the dam.

The tile sizes were generally two inches square or smaller. With regard to color, the whole spectrum was represented. They usually wore a flat, non-glossy finish that was the same throughout the thickness. As for shapes, there were square, rectangular, and octagonal tiles. Thickness measured a pretty consistent 1/4 inch.

Flat stones; a flat body of water; no further thought required. Whether the tiles had too sharp of edges to skip well across the surface of the water or not, needed to be discovered by each youngster who passed by the area. One could bet their best shooter marble on the outcome. The wisest skipper knew that the best results as far as the number of skips achieved seemed to be accomplished when the water was glass-smooth and void of wind generated ripples.

The kindly Mr. Staub might have wondered how long it would take before the bottom of the pond was better paved than his driveway. His choice of paving stone a few years later was locally quarried Trap Rock.

Laws of Physics be dammed, neither glass marbles nor ceramic tiles could come close to matching good old fashioned, river tumbled stones (of which the area was void) for their excellent skipping qualities.